Power of Publication: The Ozone Story

In 1985, Joe Farman, Brian Gardiner, Jonathan Shanklin and their team noticed something concerning about the ozone layer. They submitted a paper to Nature revealing this alarming discovery. Over the next 30 years, the findings first detailed in this paper made the world take action. Today, the ozone hole is closing. Discover how research spurred people and policymakers to do things differently and solve an urgent environmental problem.

1970–1980s

Studies in the 1970s and early 1980s highlight the risk posed by CFCs (a man-made gas used in aerosol sprays and for refrigeration) to the ozone layer. However, low emissions levels at the time mean that models predict limited damage.

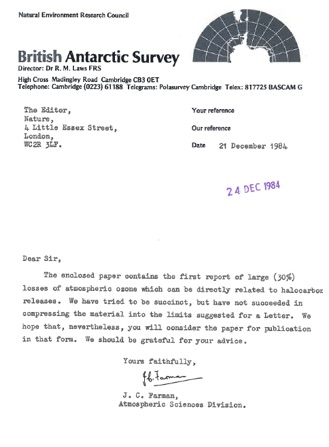

December 1984

Joe Farman, Brian Gardiner, Jonathan Shanklin and their team at the British Antarctic Survey submit a paper to Nature reporting losses of atmospheric ozone related to halocarbon releases. It would be one of the greatest geophysical discoveries of the 20th century.

March–May 1985

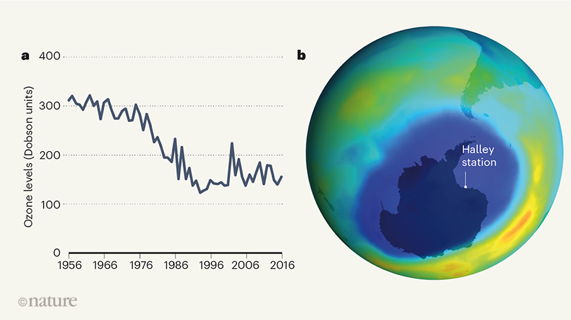

The research paper is accepted and published in Nature. It details large losses of total ozone in the Antarctic, revealing seasonal ClOx/NOx interaction.

June 1986

Further research submitted by Susan Solomon et al. clarifies the negative impact of CFCs on ozone depletion.

September 1987

The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer is adopted. This landmark agreement regulates the production and use of nearly 100 ozone-damaging chemicals.

1989

The Montreal Treaty becomes the only UN treaty ever to be signed by every country on earth.

1991

A multilateral fund is set up to provide financial and technical aid so that all countries can comply with the Protocol.

2007

The Montreal Amendment is signed. All countries agree to faster phasing out of HCFCs – a group of particularly potent greenhouse gases.

2016

The Kigali Amendment sees some countries agree to start reducing use of HFCs (compounds with high global warming potential) from 2019. This is projected to avert 0.5°C of warming by 2050. (World leaders discuss ban of climate-busting refrigerants | Nature)

2050

If we continue to follow the science – and the Montreal Protocol – the ozone layer is estimated to recover fully by mid-21st century.